Over the past two years we have worked with Helping Hands at Bybee Lakes Hope Center, Metro on the Protect and Restore Bond, the State of Oregon to build a website with info on Covid-19 and crowding potential, and Guerrilla Development to design a large-scale Black Lives Matter mural to wrap two new buildings on NE Sandy in Portland.

Integrating Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

The integration of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) into design and planning projects has been a long time coming. As designers and planners who are listening to and participating in the public discourse, we think about these issues often; unfortunately, it is less often that we have the opportunity to ensure processes and outcomes in our work that meaningfully increase representation of community voices, mitigate environmental burdens, or redress the inequitable apportioning of resources.

Part of the reason for this has to do with the entropy that surrounds any kind of large societal change, and part of it may be that it is not always clear that the design professions are in fact well-situated to effect change in the most impactful ways. Inequality is systemic, and some would argue that it is a feature, not a bug, of our economic system. If we are honest with ourselves, we acknowledge that design and planning do not primarily work at the level of these fundamental features of society.

Some doing this work add a fourth term to DEI— justice—and use the shorthand JEDI. Justice means “to dismantle barriers to resources and opportunities in society so that all individuals and communities can live a full and dignified life.”[1] With this addition, what could be taken as a set of best practices, passive “do no harm” rules, or (at worst) a list of check-boxes, is forced to take an active role.

A third reason that JEDI is not integrated into our fields as often as it could be is simply that it is complicated, and methods to do so are not always readily available. We are building the bicycle as we ride it. It takes a great deal of intentionality on the part of both clients and consultants to make space in a contract to design the means of doing so. DEI is increasingly a designated office with full-time positions in our institutions, and firms led by Black and Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) specializing in community engagement and equity analysis are building models that bridge this gap.

In the design and planning world, people tend to think that these equity issues are only relevant for a narrow set of project types. Public projects like city parks, municipal buildings, community centers, and schools often have robust DEI parameters, because governmental clients have more developed standards with stronger mechanisms to enforce them.

Regardless, there is no project type that does not impact people, even if it is a private corporate campus or a remote wilderness area.

Seeking Equitable Outcomes in Conservation Planning

In the context of conservation planning, land acquisition management decisions don’t just affect populations of native plants and wildlife, or the functioning of ecosystems– they have real and tangible effects on people’s lived experience.

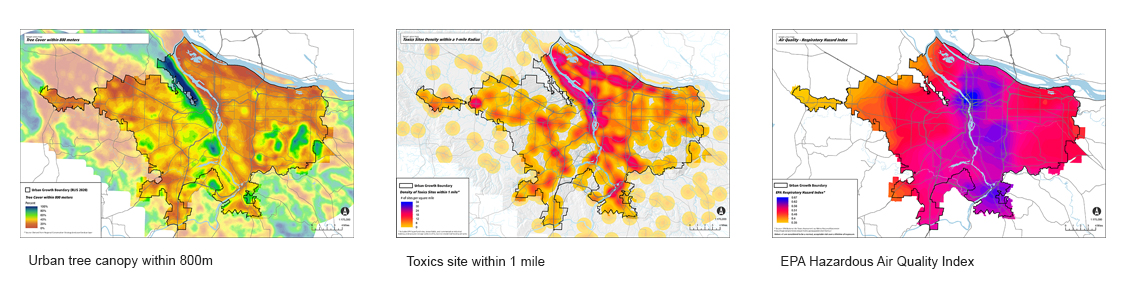

The outcomes of these decisions can mean who has access to these special places for active and passive recreation, and who doesn’t feel welcome. Which neighborhoods experience less intense extreme heat events because of the tree canopy these places provide, and which neighborhoods see vulnerable people suffering the worst consequences? Where are kids growing up with higher rates of asthma because of patterns in hazardous air quality and recurrent flooding, and where are they untroubled by these ailments? Who gets hired for stewardship positions, leading to career paths in sustainability fields? Which residents get to experience the benefits of ecological amenities, and which are displaced by them?

These kinds of questions are related to equity in conservation planning. If we don’t ask them at every step of the way, the answer will almost always be: the same people that have always enjoyed these benefits. The same people who have always borne the brunt of environmental burdens. The same people who have always been disenfranchised.

We have been thinking about these impacts a lot recently during our involvement with Oregon Metro’s refinement process for the 2019 Parks and Nature Bond Measure. Voters have approved $475 million to protect clean water, restore fish and wildlife habitat and provide opportunities for people to connect with nature close to home, and Metro is now deciding how to spend those funds in accordance with the Bond criteria. We know that endeavors like this can’t solve the intractable problems our communities face on their own, but they do have the potential to reinvest in areas that have suffered from historic disinvestment and improve ecosystem function in areas that have been burdened with disproportionate harms.

The difference is in the process, and in the results. To start with, any organization embarking on this effort must analyze the power dynamics amongst their stakeholders and community members, and ensure that those with the least influence are given a seat at the table. To find success, the organization needs to model the system they set out to change, set measurable objectives, and assess the impacts of their efforts. It is the responsibility of influential organizations to be the ones to show up, listen, and follow through on the promises they’ve made.

Assessing Urban Ecology in the Greater Portland Metro Region

Through the Bond refinement process, Metro is demonstrating their commitment to fulfill that responsibility. In contrast with the previous Bond that passed in 2006, this Bond explicitly includes top-level community engagement, equity and climate resilience criteria that apply to all projects to be funded. Metro’s criteria for community engagement and racial equity of Bond projects emphasize engagement with communities of color, Indigenous communities, low-income and other historically marginalized communities in all aspects of the process, including the planning and prioritization phases. They require Metro to demonstrate accountability for impacts to these communities, and strategize on how to prevent or mitigate displacement and/or gentrification from bond investments.

The strategy to fulfill these criteria involves multiple stages and levels of community and stakeholder engagement, as well as efforts to analyze and communicate the impacts of investments made within each program area. As part of the Information Gathering phase of the Protect and Restore program area, ecological assessments of 24 different target areas across the Metro region are currently underway. These assessments gather information to support development of land acquisition priorities in the Protect and Restore Land program area of the Bond, and Knot’s team is working with Metro staff and Indigenous community advisors on an ecological assessment of all land within the existing Urban Growth Boundary.

As the largest single Assessment area, land within the UGB has a high potential to contribute to the agency’s objective of advancing equity. This area is host to the highest levels of racial and economic diversity, with a great range of community needs and exposure to environmental burdens that disproportionately affect BIPOC and low-income people.

Knot has built special topic analyses to complement the standard assessment, adding depth to the characterization of the landscape and facilitating the application of an environmental justice lens as the land acquisition refinement process unfolds. These special topics (three of which are shown above) map the distribution and density of urban tree canopy, impervious surfaces, extreme heat exacerbated by the Urban Heat Island effect, flood risk, toxics sites, and air quality.

Phase 1 of the Protect and Restore Bond Refinement will be complete by mid-September 2021, and Knot is engaged to continue this work in the next phase, which will synthesize information gathered through assessments of all 24 target areas while developing and applying a custom environmental justice lens.

[1] Definition from the J.E.D.I. Collaborative website https://jedicollaborative.com/